See Christ is Risen! Part 6a. Who was the first witness?

In this second half of lesson 6, Dr. Jeannie continues her discussion of 1 Corinthians 15, and the correct understanding of the doctrine of Christ’s two natures as it is reflected His Resurrection.

Christos Anesti! Christ is Risen!

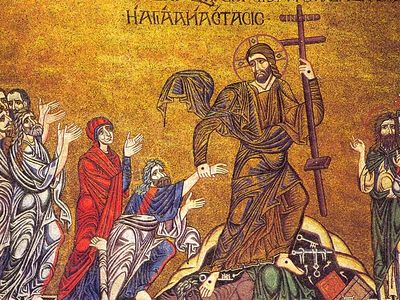

Christ is Risen from the dead, trampling down death by death and upon those in the tombs bestowing life.

St. Paul’s humility

In 1 Corinthians 15, verses 8 and 9, is Paul’s testimony that Christ was also seen by Paul, who was “one born out of due time.” And we said that this is Paul’s way of saying that he was not among the original apostles. He also was not one of The Twelve. He never knew the earthly Christ and didn’t follow His ministry, and also that he was “the least of the apostles” because he was “not worthy to be called an apostle” since he had “persecuted the Church.”

Chrysostom also talks about this and the way Paul expresses it, and here are Chrysostom’s thoughts: “This blessed man first declares his own misery and then utters that lofty expression. This then he does partly to abate the offensiveness of speaking about himself, and partly that he might hereby recommend to their belief what he had to say afterwards. For he that truly states what things are discreditable to him and conceals none of them, such as that he persecuted the Church and that he laid waste the faith does hereby cause the things that are honorable to him also to be above suspicion.” So first Paul talked about his faults, that he was the least of the apostles, that he’s not worthy, that he persecuted the Church, thereby saying the truth about himself, and saying that if he’s going to say the truth about himself and the things he had done, then they should also believe the truth of what he was saying about his experience of the risen Christ on the road to Damascus. Then Paul continues by saying, “But by the grace of God, I am what I am and His grace towards me was not in vain but I labored more abundantly than they all yet not I but the grace of God which was with me”; and in verse 11: “Therefore whether it was I or they, so we preach and so you believed.” So Paul was not one of the original apostles but he includes his own experience of the risen Christ, because he wants to be considered an apostle and wants to affirm that his experience of the risen Christ is in line with the other apostles that Christ rose from the dead. His testimony is the same as theirs. Maybe he wasn’t one of the original, but he says, “Whether I or they, so we preach”, that is, that we preach the same thing and so you believed our testimony.

I think it’s beautiful there that Paul says, “by the grace of God, I am what I am and His grace towards me was not in vain.” This is something that we all ought to think about, because God has also shown great grace towards us and we should be wondering whether not His grace towards us has been in vain or not. Certainly sometimes it is, but hopefully not over the course of our lives. But it certainly wasn’t with Paul. The grace that God showed him certainly wasn’t in vain. And Chrysostom comments about this. And here’s what Chrysostom has to say: “For if he labored more, the grace was also more. But he enjoyed more grace because he displayed also more diligence, and these things, when we hear, let us also make open show of our defects, but of our excellencies let us say nothing. Or if the opportunity force itself upon us, let us speak of them with reserve and impute the whole to God’s grace, which accordingly the apostle also does ever, and ever putting a bad mark upon his former life, but his after state imputing to grace, that he might signify the mercy of God from every circumstance. For His having saved him, such as he was, and when saved, making him again such as he is. Let none accordingly of those who are in sin despair and let none of those in virtue be confident, but let the one be exceedingly fearful and the other forward, for neither shall any slothful man be able to abide in virtue, nor one that is diligent be weak to escape from evil.”

There are so many things mentioned in that beautiful statement of St. John Chrysostom. First let’s mention the first thing that he says; let’s note this. He says that because Paul worked harder, he also received more grace, and the more grace he received the more diligence he showed. Now what Chrysostom is expressing here is a very, very important concept in Orthodox theology called synergy—that we cooperate with the grace of God, and the more effort we put in the more God blesses us with His grace; and it is a relationship that is constantly growing. And how much we respond to God also affects how God responds to us, and this is a very important concept. Perhaps we’ll have the opportunity to discuss it more in the future. This is something which is extremely important. It’s presumed in much of Orthodox theology and certainly in our spirituality, but how this works isn’t usually spoken of directly. It is a great mystery how it works, but we don’t impute everything to our efforts and we certainly don’t say that our efforts count for nothing. But somehow there is a relationship, a “co-working” (that’s what the word “synergy” means) between us and God. So Chrysostom is referring to that here. Paul received a great deal of grace but not just because of God only. God gave him the grace but then also Paul used that grace, he displayed more diligence, etc. And also Chrysostom notes how Paul speaks. He openly confesses his weaknesses, his past life, but is reluctant to take credit for any of the good things he has done. So there we see the humility of St. Paul, how everything bad he attributes to his own mistakes, and yet everything good he attributes to God. And lastly, in this quotation St. John Chrysostom reminds us that even if we are in sin we shouldn’t despair, and yet those of us who are virtuous should not be confident and lazy, because the slothful man will not be able to remain in virtue, nor a diligent man remain in sin. A diligent man can “escape from evil”—that’s what Chrysostom says.

The Resurrection of the dead in the body.

Now let’s read the next section of the text of 1 Corinthians 15 beginning with verse 12: “Now if Christ be preached, that He rose from the dead, how say some among you that there is no resurrection of the dead? But if there is no resurrection of the dead, then Christ is not risen. And if Christ is not risen, then our preaching is empty and your faith is also empty. Yes, and we are found false witnesses of God because we have testified of God that He raised up Christ whom He did not raise if in fact the dead do not rise. For if the dead do not rise, then Christ is not risen. And if Christ is not risen, your faith is futile, and you are still in your sins. Then also those who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished. If in this life only we have hope in Christ, we are of all men the most pitiable.”

So let’s begin with that first verse, verse 12: “Now if Christ be preached, that He rose from the dead, how say some among you that there is no resurrection of the dead?” So this goes back to what I was saying before, and Chrysostom makes the same observation: That it is very clear from this passage that the Corinthians believed that Christ rose from the dead, and of course every time I say, “rose from the dead,” I mean in the body. There is no such thing, and Chrysostom makes this point also, of rising from the dead with His soul, or His spirit rises, or His spirit lives on but not the body, because it’s the body that dies. So when we say that Christ rose from the dead, implicit within that is the concept of the resurrection of the body—let’s just make that perfectly clear. Chrysostom also makes this point.

So it’s clear that the Corinthians believed all of the apostolic witness that Christ rose, but they did not believe that they themselves will rise. They didn’t believe in the general Resurrection. And the reason for their disbelief was because of the prevailing conceptions about the soul and body in Greco-Roman society. This period of history is called the Hellenistic Age. This means that even though the Romans were ruling the world (this is the Roman Empire now), Greek thought ruled the thoughts of people. Greek thought, Hellenism, had influenced the way people thought, so the Romans adopted Greek thought, Greek philosophy, Greek culture, the Greek gods, Greek architecture. This is called “Hellenism.’ The Hellenistic era means society is not directly under Greek rule, but it is so influenced by Greek thought that we call this the Hellenistic Age. So during this period of time, Greek philosophy was very, very influential in determining how people thought about things, what kind of presumptions operated in society. And Greek philosophy served for them pretty much the same function as science does for us today. So for them an idea had to fit the concepts they had assumed as part of their Hellenistic way of thought. These concepts really came from Greek philosophy, but they didn’t necessarily identify it as “philosophy.” They just accepted these things as givens, as obvious. “Of course it’s a fact that the body can’t rise!” “There is no such thing—it’s an obvious fact.” In the same way that we have trouble accepting an idea if it doesn’t seem to fit our norms of science or history, if we can’t find absolute proof, then we have trouble accepting it—in those days they had the same problem. Someday, our ideas of science will be found to be not scientific and someday people will say, “Oh, I can’t believe that people thought this way back then, a 100 years ago or 200 years ago!” They will have trouble understanding how we could believe some of the things that we accept today. But science changes; and in antiquity the reigning mode of thought was Greek philosophy, especially Platonism, and this very strongly influenced the Greeks’ belief that a body could not rise. Now, Platonic philosophy was basically dualistic, and Platonism just was the dominant way of conceiving about the natural world. Dualism was the belief that the physical world was an imperfect copy of the spiritual world, where everything was perfect. The physical world, this life, was inferior to the spiritual world. The body was inferior to the soul, because the body needs to be fed, needs to be cleaned, it needs to rest, gets tired, it ages, it gets ill, it dies. Meanwhile, the soul does not suffer from these kinds of ill effects.

Now, even though the Greeks believed that the body was inferior to the soul, at the same time they were great admirers of physical fitness. They had the Olympic games. They had the beautiful statues as perfect physical specimens. They admired the ability of the body to perform and to be beautiful and healthy and all of these things. Yet they recognize that the body is inferior to the soul because it has certain needs: you get tired, you need to eat, you need to sleep—all of these things. The soul meanwhile doesn’t suffer these kinds of limitations. It is not encumbered, except by the body which houses the soul, or the mind. So the mind can go places and do things even when the body is feeble, ill or old. So the conception was that the body is like a prison for the soul, and when you die it will be great, because your soul will be freed. It is released from the constraints of the body and it has nothing to hold it back. So according to this view, which was the prevailing view of the human person at the time, no one wanted a resurrection of the body! They only wanted the soul. They presumed that the soul lived on, but they certainly didn’t want the resurrection of the body, because then your soul would be trapped in the body again. So this was what Paul was fighting against, and frankly what all of the apostles had to contend with.

And so, earlier in this same book, 1 Corinthians, when Paul is talking about the crucifixion, he says “We preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block for the Jews and foolishness for the gentiles,” or “the Greeks.” Why “foolishness”? Because they couldn’t believe in the resurrection of the body: it was too foolish for them. So when Paul went to Athens—and this story is told to us in the book of Acts—he went to meet the Athenian council, the rulers of the city of Athens. They were meeting on the hill below the Acropolis, called the Areopagus. Paul went and preached Christ to them and they were very open, and they listened to him, and everything was going fine until Paul mentions the Resurrection. Then most of them started laughing at the Resurrection of Christ, because it did not make sense. Why would you want that? This is contrary to what they would think, that you would want a resurrected body.

Now, you didn’t have to be a philosopher to operate with these kinds of presumptions. Just as today, you don’t have to be a historian or a scientist to be influenced by that mode of thought. Today we are always comparing beliefs and concepts to what can be proven in science or by history, “Do we have any proof?” We always think in terms of proof; proof of this, proof of that, does it make sense scientifically. So we measure everything against history and science. But in those days they measured things against what people believed was absolute truth, and that was not science but philosophy. Rveryone knew these concepts, they were general norms and they were accepted in society as proven facts and almost no one questioned them. They would think, “Well, everyone knows the soul is inferior to the body,” and so on. So these things were cultural norms. We also have our cultural norms. They had their cultural norms and, at least in the Roman Empire, this was the norm.

Perfect God and perfect man.

Now let’s move ahead a couple of centuries to the council of Nicea. The Council of Nicea, the first Ecumenical Council, affirmed the complete Divinity of Christ, that is that Christ was perfect God and perfect man, fully human and fully divine, equal to the Father—the Son was homoousios, one in essence with the Father. This was affirmed in the fourth century in 325 at the Council of Nicea. The next question that was raised according to their minds, because their minds were influenced by Greek philosophy, was how the humanity and the divinity could be united in the one person of Christ, since humanity and divinity are entirely different in their nature. This was happening toward the end of the fourth century. (There is a connection between this and the Resurrection, trust me.) So at the end of the fourth century, the late 300s, there was a bishop named Apollinaris, who said that—in terms of the connection between the humanity and the divinity of Christ—the Logos, that is the Son, the divinity of Christ, had replaced the human mind or the human soul of Christ. But this view was rejected, and the person with very famous reply to that heresy was St. Gregory the Theologian, whom the West calls Gregory of Nazianzus. He said about this, “What has not been assumed, has not been healed.” That is, if the Logos, the Son of God, did not take on human nature in its completeness, the full human nature, if He was not incarnate as fully human with a human mind a human soul, then our human minds and souls were not healed by the Incarnation and the Resurrection of Christ. St. Gregory said, “What has not been assumed, has not been healed.” He argued for the complete humanity of Christ, that Christ was fully human in every respect. So what does this have to do with the Resurrection? Well, it has to do with the Resurrection because to claim that only the soul of Christ rose or the spirit of Christ and not the body—because this conflicts with our scientific or historical sensibilities—we could apply the same point that Gregory the Theologian had made.

Today, we have an entirely different problem from what Paul was addressing at Corinth, and even what St. John Chrysostom was addressing when he was commenting on this chapter. Because, you see, Paul is saying that the Corinthians believe that Christ rose in the body. They just didn’t believe that they would rise. But we don’t have that problem. And as a matter of fact, that was still the problem at the time that Chrysostom was preaching and explaining this chapter, so most of what Chrysostom says in his sermons (and he gave five sermons on this one chapter in 1 Corinthians 15—five sermons), was related very closely to what Paul was saying, because Greek philosophy was operating in Chrysostom’s time and Chrysostom’s culture. Chrysostom was affirming the fact that Christ had a body, because there were many, many heresies that believed that Christ did not actually have a physical human body. Today we don’t have that problem. Today, just about everybody believes that Christ existed as a human person, but many people do not believe that He was God. And today we also have the opposite problem of what the Corinthians had, because the Corinthians believed that Christ rose in the body but that they would not. We have the opposite problem because many people, including people who identify themselves as Christians, do not believe that Christ rose from the dead in the body. They say He rose in spirit; the apostles remembered Him, maybe the soul rose but not the body, because this conflicts with our ideas of science and history. So we could apply the same rationale that St. Gregory had made when he said, “What has not been assumed, has not been healed.” We can say, “What has not been raised has not been healed.” When the Logos was incarnate (the Logos is the Greek word for “Word”; that comes from the first chapter of the Gospel of John), when the Word or the Son of God was incarnate, He became fully human with a human soul and a body in order to redeem, to sanctify, to elevate our human nature. All of it! The whole of our human nature. That’s why he was incarnate as a whole person, an entirely human being, he was hoomoousious with us, one in essence with us in our humanity, the way in His divinity He was one in essence with the Father.

Now, if the body of Christ did not rise, then the whole man was not saved by Christ. But we affirm continually in the life of the Church that the whole person is sanctified by the grace of God. So when we receive Holy Unction, it is for the healing of body and soul. The whole person is also sanctified by Holy Communion. Holy Communion is sanctification of the soul and the body. We are united body and soul to Christ through Communion.

When we baptize someone, we immerse the body. Why do we do that rather than just having someone assent to certain beliefs and then just call it baptism? Or, you know, just say the Creed and you’re a member of the Church. No. We immerse the body, because it’s the temple of the Holy Spirit, and the body is sanctified in baptism. The whole person is healed, the whole person is saved. Why? Because the whole person is a creation of God, and therefore the whole person must rise. It’s inconceivable that only the soul would rise—either only Christ’s soul or just ours. So why should only the soul rise? Because if you say that then you’re suggesting that only the soul was healed and the rest of us wasn’t healed. But Adam and Eve did not simply sin in the soul, they sinned in the body too. They took the fruit and they ate it. That was a deed. It was not just a rebellion in the mind. And therefore the effects of the Fall of mankind were suffered by the whole man. Not only did Adam and Eve’s souls suffer, but there were physical effects from the Fall. Now they had to work for their food, “by the sweat of your brow shall you earn your bread.” Now Eve would experience pain in childbirth. Now women would be dominated by men. Now there would be illness in the world, there would be death, etc. So the effects of the Fall affect both the soul and the body, and therefore it was imperative that Christ be incarnate as a full human being with a human soul and a human body, and it was imperative that He rise both in the soul and in the body. The human being was created by God as what we call a “psychosomatic whole.” Either the whole thing rises, or nothing rises. To deny the physical resurrection of Christ is to deny the humanity of Christ. Can you see that?

We should know Orthodox theology before talking about it.

So it’s very important that when we talk about these things we understand what we are talking about. We can’t simply speculate about such things. We have to realize that to deny the physical resurrection is to deny the humanity of Christ and therefore to deny our salvation. There are consequences to what we say. So it’s important that when we think about these things, that we should think about them, we should learn about them, we should study theology. But we should not engage in discussions on theological matters or give our opinions if we don’t know what we’re talking about, because this is not a pursuit to be entered into lightly, like “armchair” theologians. This is not a matter of speculation. We can’t pick and choose and say, “Well, I’m a Christian but I don’t believe that Christ rose in the body.” This is serious business, because doctrine really matters; there are many ideas that seemed logical at first sight, many heresies which seemed to make sense when you first heard them, but they’re heresies. And a denial of the Resurrection is one such thing. It has implications for our salvation, and if you don’t understand that then you really have no business expressing your theological views, because if you lead someone astray with your argument then you are in fact responsible for that person.

So if Christ did not rise, then we also will not rise. And if we cannot rise, then Christ also did not rise. To deny our future resurrection is to deny Christ’s resurrection. And conversely, to deny Christ’s resurrection is to deny our resurrection and to deny eternal life itself.

I think this is probably a good place to stop. There is much more to say about this, and I want you to understand that next time, when we continue, I’m going to continue along these lines on some of the theology of the Church. I hope it is ok with you that we talk with you about the theology. I think it’s important to say what else Chrysostom has to say about the theological effects of the denial of the Resurrection, and we will also talk about some of the other parts of 1 Corinthians 15, which are very interesting; for example, what Paul has to say about Christ being the “first fruits” of the Resurrection. Why does he say this? Also Paul mentions a very peculiar thing when he talks about being “baptized for the dead.” What did Chrysostom have to say about this? So I hope that next time we will complete our series by finishing up with Paul and Chrysostom on 1 Corinthians 15. There’s a number of very interesting issues to discuss next week, and we will continue then with our discussion on 1 Corinthians 15. But for now, let’s close with our prayer.

“Christ is Risen from the dead, trampling down death by death and upon those in the tombs bestowing life”. Alithos Anesti o Kyrios! Truly the Lord is Risen!

Presbytera and Dr. Jeannie Constantinou’s podcasts can be found here.