A Tradition of Linguistic Diversity in Orthodox Alaska

RTE: Mikhail, will you please tell us about the Alaskan native language project and how it developed?

MIKHAIL: First, I’d like to thank you and the staff of Road to Emmaus for your interest and enthusiasm for the Alaskan Orthodox texts project. We’ve received an outpouring of goodwill and support from around the world: Alaska, Finland, Russia, Latvia, Hong Kong ... we thank God every day for the encouragement it has provided us and for the growing worldwide audience who are learning about our Orthodox brethren in Alaska.

Father Geoffrey Korz, the rector of All Saints of North America Orthodox Church in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, is the spiritual head of this effort, while my wife and I have been blessed to research and publish the original Alaskan language texts. I’m of mixed Mediterranean and Eastern European background, and only came to Orthodox Christianity in my mid-twenties, as did my wife who is of Chinese heritage. I currently serve as a church reader in Toronto. Some people say that Toronto is the most multicultural city in the world, and I think that has had a great influence on my love of languages and travel. Before coming to Orthodox Christianity, I had the opportunity to travel and live in Russia, Finland, Greenland, and Canada’s Arctic territory of Nunavut. Part of my experiences in Russia and Finland were key to my conversion to Orthodoxy, while my time spent in the Arctic regions of Greenland and Canada engendered a love and passion for the north.

One day, in the winter of 2005, I was visiting Father Geoffrey in Hamilton (about an hour’s drive west of Toronto), and knowing my love of historic books and the Arctic, he gave me a book called Alaskan Missionary Spirituality by Orthodox author Father Michael Oleksa. The book is essentially a collection of documents, letters, and journal entries – translated into English – of the most well-known people associated with the Orthodox Christian mission to Alaska in the 1800’s ... this would include St. Herman of Alaska, St. Innocent Veniaminov, St. Jacob Netsvetov, and others. This collection and the excellent commentary discuss the efforts of the mission to reach the native peoples in their own languages; to baptize their venerable cultures into their natural fulfillment in Orthodox Christianity. Anyone who reads the life stories of St. Innocent and St. Jacob is sure to learn about their heroic exploits and their incredible translation work into the native languages of Alaska.

In fact, in everything I read about these saints, it is obvious that their work in Alaska paralleled that of Sts. Cyril and Methodius in evangelizing the Slavic peoples. We all know of the rich Slavonic literary legacy of Sts. Cyril and Methodius, but where, I wondered, was the physical evidence for the work of Sts. Innocent and Jacob in Alaska?

RTE: Years ago, I asked this same question of Kodiak natives, and they told me that they knew of nothing except some very old Slavonic-Aleut service books, still in use in small churches in the Aleutian Islands. They had been printed in the late 1800’s, under the influence of St. Innocent’s mission. How were you able to track down these sources?

MIKHAIL: I looked on the internet and found many Orthodox sites in Russian, Serbian, Greek, Albanian, even Orthodox Brazilian Portugueselanguage sites, but nothing in the Alaskan languages. Everyone seemed to know about the Alaskan native translation work, but nobody on the internet seemed to know where these texts were. After reading about the courageous contemporary struggles of the Church in Alaska (as discussed on www.outreachalaska.org/history.html), I prayed to St. Herman to help me, according to God’s will, to see what could be done to assist Alaska. His Grace Bishop Seraphim of Ottawa and Canada (Orthodox Church in America), gave his blessing for this project, and off I went into the unknown.

At this point, a stroke of inspiration appeared out of nowhere, and using the internet, I found a treasure trove of rare Alaskan Orthodox texts scattered around various repositories throughout the United States. Many of these hadn’t seen the light of day since the early 1900’s. Through the dedicated work of many people, especially the staff at the Alaska State Library Historical Collection, I was able to obtain copies of the texts, and set to work typing them out.

However, I soon ran into the difficulty of trying to typeset Old Slavonic-looking letters which were especially invented by the missionaries for the Alaskan languages (particularly, Aleut and Kodiak Alutiiq).

After more prayers to St. Herman for God’s help, it appeared possible to come up with a scheme of creating “font composites” by superimposing existing computer fonts on top of each other so as to create the necessary characters.

The technical details aren’t that interesting, but the fact is that the Lord provided the right answers at the right time. However, many of the copies I was working from were difficult to read as the originals had decomposed somewhat, and in many places were completely unreadable. What to do? Dictionaries for these languages weren’t readily available, and certainly not in the 1800’s Cyrillic alphabet (since all Alaskan languages converted to the Latin-based, English-type alphabet by the 1970’s). I called the Russian Orthodox Diocese of Alaska, and they directed me to Father Paul Merculief, a fluently-speaking Aleut archpriest and foremost linguist. To my amazement, he had a nearly complete library of Alaskan Orthodox texts, but had met with little success in typing them out due to the “font composite” problem I mentioned earlier (i.e. the use of specialized characters that didn’t exist in any other languages).

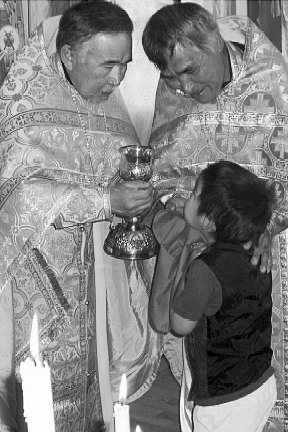

Father Michael Oleksa, Chancellor of the OCA's Diocese of Alaska, reads while Father Marc Dunaway, rector of St John Cathedral, and priests several local Orthodox churches listen

Father Michael Oleksa, Chancellor of the OCA's Diocese of Alaska, reads while Father Marc Dunaway, rector of St John Cathedral, and priests several local Orthodox churches listen

We’ve had much assistance along the way: historians, scholars, archivists, Alaskan native peoples, and the prayers and support of His Grace Bishop Nikolai of Sitka, Anchorage and Alaska (OCA), which has been a constant source of encouragement for us.

Very recently, the Lord blessed us with another cache of handwritten manuscripts which had never been published. Although many of these are in very bad shape for transcription, some of the better surviving texts are now being prepared for publication for the very first time. One of these is an Aleut-language sermon handwritten by St. Jacob Netsvetov himself, as well as translations of the Holy Gospels and Catechisms. To look upon the words of St. Jacob’s ornate calligraphy, to touch his handwriting, is to touch a holy relic. It is a blessing which we are not worthy of, but have been mercifully allowed to behold. If God wills, many of these should be available on-line at www.asna.ca/alaska in the years to come.

RTE: Your experience is very close to that of Fr. Elie Khalife, who is locating and cataloguing the manuscripts of the Antiochian Orthodox Patriarchate that have been scattered around Europe. I remember him saying that Horologions and Psalters are the most used books in existence. They were read page by page at every service, every day, for centuries, and that in working with them you know that you are touching books through which thousands of people have sanctified their lives. Saints have used them or even written them.[1] As you say, these truly are relics.

MIKHAIL: It’s interesting you should mention that. Fr. Geoffrey and I were just discussing this idea during a road-trip to a monastery we took last month. For me, it is all a matter of love for God in His Saints. Before I became Orthodox I had an iconoclastic fear of icons and relics of any kind. Yet, once, a number of years ago, on a very rough flight over the mountains of Bolivia, I found myself kissing a wallet-picture of my beloved who later became my wife. Why? It was a way of expressing love.

This was not idolatry. Kissing the photo of my beloved, I thought, “If I never see you again in person, I will treasure these few moments I have to see a photo of your smiling face.” Love, that was all. In a similar manner, if we have the diary of a loved one who has departed this life, would we not kiss this diary? Would we not hold it tenderly, read it with attention, and restore it, so as to preserve the memory of the one who wrote it? If we love the saints, especially the holy ones who have walked among us in our lands, would we not similarly wish to preserve and beautify their labours of love for the Lord? At the feast of Pascha, we sing “Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life.” The saints are alive in Christ, though we do not usually see them (although this is sometimes granted by God) — why then would we refuse to show them our love? The restoration of holy writings, like the making of icons, is a form of prayer with which we, the Orthodox faithful, connect with those who have “fought the good fight” and “entered into the joy of our Lord.”

Manuscripts, and other holy relics, are the physical proof that a saint lived with us, worked among us. My greatest fear was that someday someone might say, “I don’t believe that the Orthodox Christians showed love for the native Alaskan languages and cultures. Show me proof!” And we would have nothing to show ... Now we may face those who accuse the Orthodox, and say, “Look, and be silent, here is your proof!” Actually this is a present reality ... anyone can do an Internet search and find various bitter, hateful writings aimed against the history of indigenous Orthodoxy in Alaska. Now, the voice of indigenous Alaskan Orthodoxy cannot be ignored. The proof is in print, and it is there for all to see, thanks to God.

RTE: One of the revelations in reading native Alaskan Orthodox history such as Alaskan Missionary Spirituality, or From Mask to Icon: Transformation in the Arctic, is how Orthodoxy was very much initially embraced and then kept alive by the native peoples, sometimes without seeing a priest for years. Twenty years ago, I remember Aleuts from Kodiak simply saying, “To be native is to be Orthodox.”

MIKHAIL: Yes, indeed. Fr. Michael Oleksa goes into great detail about this in his book Orthodox Alaska — how many elements of the pre-Christian Alaskan worldview were not abolished, but rather fulfilled in Orthodox Christianity. A number of themes such as cyclic time and symbol as expressions of true reality, show direct parallels.

An example given in Orthodox Alaska is that of a group of hunters in kayaks trying to catch a giant whale, upon which they depend for food and life. Armed only with harpoons, the hunters realize that they have no chance of bringing down this powerful whale which could either a) crush them, or b) swim away. Only by voluntary self-sacrifice does the whale allow itself to be caught. This worldview contains a glimpse of Christ’s voluntary self-surrender in the garden of Gethsemane.

Another example cited is that of the role of the pre-Christian shaman, which could only be assumed by one who had undergone a ritual death and re-birth, someone who had gone to the land of spirits and returned. Alaskan peoples could very clearly grasp the truth of Christ’s necessary death, descent into Hades, and resurrection for the salvation and transformation of their souls. Without baptism, as participation in Christ’s death and resurrection, humans would be separated from the fullness of reality.

The pre-Christian Alaskan worldview was maximalist in its view of ritual action participating in the eternally-significant events of “those days” when the condition of man was less fragmented, less broken. Ritual actions upon leaving/entering one’s home and the layout of traditional native dwellings, strive to re-present the cosmos in microcosm. Similarly, in Orthodoxy, our making the sign of the cross, our liturgical blessings of water, wine, and oil, Church architecture, iconography — everything we do is a means of harmonizing and directing our heart toward God in Christ. In Orthodoxy, there is no artificial separation between spiritual vs. physical, faith vs. works. Everything we do, everything we are, is, in the Patristic understanding, a holistic unity of body, soul, and spirit.

When Christians affirm that Holy Communion is the true body and true blood of Christ — a true re-presentation of the Last Supper — the Alaskan worldview would say, “Of course it is! How could it be any different?” The events of nearly 2,000 years ago are made present in their fullness in every Divine Liturgy. These are things that the faithful Alaskan Orthodox know experientially, but something which many learned scholars and academics fail to understand. But then, such wisdom was given to the simple fishermen — the Holy Apostles, and not to the wise of this world. (Acts 2-5, I Cor:1) Historically, the monks of the original Valaam mission to Kodiak in 1794 defended, with their lives, the indigenous Alaskans from the greedy practices of the government fur-trading monopoly. They fought for full-citizenship rights and dignity for the native peoples. St. Herman had to flee Kodiak for Spruce Island because of threats against his life by the fur-trading management. To this day, the local residents of Kodiak refer to St. Herman as their beloved “Apa” (grandfather), who “comforted them with earthly sustenance and with words of eternal life,” as we read in the Akathist to St. Herman of Alaska.

The saints of the Alaskan mission saw the image of God in everyone; they lived the fullness of the Gospel. They had a real love and respect for the people they ministered to. St. Innocent, like St. Nicholas of Japan, spent his first years learning the language and culture of the people among whom he was living. His preaching was one of true dialogue without compromising the truths of Orthodox Christianity, yet sensitive to the needs and cultural expression of these truths in the local setting. Baptism and reception into Church life was strictly allowed only by free choice, without monetary or other worldly incentives. Teaching was done in local languages, and leadership of the Church was quickly assumed by the local inhabitants. Initially, since there were so few clergy spread over such a vast territory, the faithful conducted abbreviated Reader/Typica services, learning the church hymns by heart. By necessity, each family had to become a church. Whenever clergy would arrive, they would find entire communities already baptized, requiring the priest to only chrismate them. Most of the Alaskan Orthodox manuscript legacy is from native clergy who rose to prominence after the 1830s, after St. Innocent Veniaminov and St. Jacob Netsvetov, the first priest of Aleut ancestry.

In fact, it is interesting to note that the majority of Tlingit, from southeast Alaska, became Orthodox only after the sale of Alaska to the U.S. in 1867 — so it had nothing to do with Russian colonial interests, as some might say. In fact, the Tlingit had every economic and social incentive to join heterodox confessions rather than Orthodoxy, except for one little thing. Whereas the heterodox sought to deny Tlingit language and culture, the Orthodox affirmed it. Even after the 1917 Russian Revolution which brought jurisdictional chaos to Orthodoxy in America, the Alaskan Orthodox Church grew because it was not an ethnic extension of a faraway place; it was the local Church.

RTE: Wonderful! How many languages and dialects are there in the native Orthodox population, and how many people still speak those languages? MIKHAIL: That’s a very good question. I cannot claim to be a scholar, but I can answer based on my experience with the texts, and having worked with the wonderful priests of the Russian Orthodox Diocese of Alaska who provided their expertise.

Numerically, the largest contingent of Native Alaskan speakers are the Yup’ik people, who number around 20,000 people, of whom 13,000 speak the language across various dialects. The Alutiiq (known as Kodiak-Aleut in Russian America) number around 3,000, of whom 500-1,000 still speak the language. Aleuts are divided linguistically into the Atkan and Eastern dialectal variants. The total population of the Aleut people is given as 3,000, with the vast majority being of Eastern-Aleut background. The Atkan-dialect of Aleut has approximately 60-80 fluent speakers, whereas the Eastern-Aleut dialect has about 300 fluent speakers. St. Innocent focused his efforts in writing for the Eastern-Aleut, while St. Jacob concentrated on developing the Atkan-Aleut and Yup’ik languages. The Tlingit population is estimated at around 17,000, of whom 500 are fluent in the language. The bulk of Tlingit literature was developed in Sitka by Reader Ivan Nadezhdin in the 1850’s, and by Fr. Vladimir Donskoi and Michael Sinkiel in the 1890’s. The Tanaina of central Alaska number around 1,000, with 100 fluent native-language speakers. In all cases, many more people understand the language but do not speak it.

The native languages all had a thriving press and literature through the 1800’s under the auspices of the Orthodox Church. However, in the late 1890’s and early 1900’s, the Protestant missions of Sheldon Jackson had a disastrous effect on native language vitality, and were clearly aimed at ripping out the roots of the Native Alaskan Orthodox cultures. Stories of faithful Aleut Orthodox being chained to the floors of their own homes by U.S. Territorial agents for speaking their language and courageously refusing to hand over their children to the Protestant boarding schools break the heart. Our native Alaskan Orthodox brothers were first-class confessors for their Holy Orthodox faith. They are heroes and defenders of Orthodox Christianity. In the midst of the turmoil of American “English-only” language policy throughout much of the 20th century, the native languages declined greatly. Much of the work of Sts. Innocent and Jacob was destroyed, but not completely. What we are seeing today is a veritable resurrection of our Alaskan brothers’ texts, their languages, their authentically Orthodox cultures. Their sacrifice is chronicled in such books as Alaskan Missionary Spirituality and Orthodox Alaska by Fr. Michael Oleksa. RTE: Sadly, the mistreatment went on well into the latter half of the 20th century. The Russian Orthodox priests who remained after the United States acquired Alaska had little influence to protect the native Orthodox, and even less after the 1917 Russian Revolution. I remember an Aleut Orthodox man who said that, as late as the 1960’s, when he was a young boy at school, the use of native language was still forbidden. If you were heard speaking it, a derogatory, humiliating sign was placed around your neck, which you wore until you heard another child speaking “native,” when you could pass the sign on to him. The child wearing the sign at the end of the day was beaten by the principal.

MIKHAIL: It is unthinkable that this type of mistreatment happened at all! In speaking with one priest in Alaska, all he said was that the people of the generation born before 1970 still bear many scars from that period, and that linguistic revival will have to come from the youth. It’s happening slowly, but now it is critically important to document those living links with the grandparents’ generation to preserve the true pronunciation of the various languages and dialects.

RTE: I’ve heard it said that the native Alaskan languages are considered among the most difficult in the world to learn. Is this true, and why? MIKHAIL: I guess that depends on who you ask! My wife thinks Chinese is easy, given that it is her first language! However, it is true that Alaskan native languages are very difficult to learn — very complex and highly developed. These languages typically have a very rich and complex phonological system, with many sounds that are difficult for Indo-European language speakers to pronounce. Nouns and verbs have intricate case-based systems for declension and agreement with prefix, infix, and suffix endings adjoined to them.

Practically, I found Eastern-Aleut to be the easiest to work with, followed by Atkan-Aleut. Conjugation of Aleut verbs, word-length, and prepositional usage tended to show closer similarity of structure to Russian than any other Alaskan native language. The Alutiiq (Kodiak-Aleut) and Yup’ik languages bear many similarities with each other, but were more difficult with their extensive use of diacritical (accented) Cyrillic. In addition, Yup’ik is a polysynthetic language which means that it has very long words that correspond to nearly-complete sentences. Each word corresponds to a densely-packed arrangement of thoughts and grammar which are held together in the one word. Every nuance of time, state, etc., tends to be reflected and compounded, which leads to a very logical, but lengthy composition of letters.

One example is from the Resurrection Kontakion of the 1st Tone. In English the first sentence is: “As God, Thou didst rise from the tomb in glory, raising the world with Thyself.” In Yup’ik, the first sentence reads: “Agayutngucirpetun unguilriaten qungugnek nanraumalriami, unguiqen ella malikluku.”

The Tlingit texts were the most difficult of all, probably due to the language’s very technical phonology and pronunciation. It is also a tonal language, which means that a word may have various meanings despite being spelled the same way, depending on the pitch of the speaker in pronouncing the word. Chinese is also a tonal language. An example of the difficulty of tonal languages is that the Chinese (Cantonese) word “siu gai yik” can mean “BBQ chicken wings” or “small chicken wings” depending on the tone of the word “siu”. Most times at the Chinese supermarket, I end up asking for small chicken wings, and the nice shopkeeper smiles at me, because he really knows that I want large BBQ chicken wings (not small chicken wings!). I just can’t “sing” the word properly. This idea of tonality applies to Tlingit as well. Unfortunately, the old Cyrillic alphabet for Tlingit didn’t represent tonality very well. These are just personal reflections, though, and I would defer to the opinion of the many native Alaskan Orthodox priests with regard to this question.

RTE: Could you enlarge now on the translating work of St. Herman, St. Innocent, and St. Jacob Netsvetov? We think of them as saints and missionaries, but most of us know little about their linguistic work.

MIKHAIL: St. Herman, as one of the original members of the Valaam mission to Russian America in 1794, was something of a pioneer in the field of Alutiiq (Kodiak-Aleut) with Hieromonk Gideon. Together, at the mission school in Kodiak, they worked on a translation of the Lord’s Prayer and began compiling the first dictionary of the Alutiiq language. One of St. Herman’s disciples, Father Constantine Larianov, later compiled an Alutiiq prayerbook which exists in manuscript form in the Alaskan Russian Church archives of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. St. Innocent Veniaminov is rightly regarded as the giant among early translators in the Native Alaskan languages. From the time of his arrival in Unalaska (Dutch Harbor, Alaska) in 1824, St. Innocent dedicated himself to the process of acquiring the language and culture of the Aleut people. As early as 1828, he set to work on translations of the Holy Gospels, but much of this early work was spoiled by errors in typesetting the text back in Russia. In 1833, St. Innocent wrote his famous Aleut-language work, Indication of the Pathway to the Kingdom of Heaven, which became an instant classic. In 1840, when he returned to Russia, St. Innocent personally supervised the printing of his texts: The Holy Gospel According to St.Matthew, the Paschal readings, a lengthy Primer/Catechism, and the Indication treatise. Most of these texts were edited by Ivan Pan’kov, a Tigalda chief and friend of St. Innocent, and were annotated with footnotes in the Atkan-Aleut dialect by St. Jacob Netsvetov. However, St. Innocent’s work wasn’t confined to Aleut, but also included Tlingit and Alutiiq. A comprehensive dictionary of Tlingit and Alutiiq was printed in 1846.

St. Innocent’s approach to language and inculturation of the Gospel was fully rooted in the Orthodox tradition, but it was a novelty among all other faith traditions. Rather than demand the use of a specific language for enforced religious indoctrination, Eastern Orthodox Christians have more often tried to sanctify a culture and its language — to bring out that which already contains the “seed of the Word” (spermatikos logos), and to encourage the native expression of the good news of Christ. This has been the experience of the Byzantine commonwealth, the African, Slavic, Georgian, Finnic, Japanese, and Siberian peoples as well. This is the gift of Pentecost that the Orthodox have shared. St. Innocent was heir to this glorious tradition and proved faithful to his calling.

RTE: Yes. And St. Jacob Netsvetov?

MIKHAIL: St. Jacob Netsvetov was born of a Russian father and Aleut mother on St. George Island in the Pribilofs, and was fully bilingual. All early Atkan dialect texts from before 1850 are the work of St. Jacob; his monumental dictionary still exists in manuscript form in the Alaskan Russian Church archives. Rather than create separate translations of St. Innocent’s texts into the Atkan-dialect of Aleut, he sought to unify the dialects by incorporating footnotes for those words which were markedly different from the Eastern dialect. His greatest glory in the Aleut literary tradition, however, is probably his mentorship of Fathers Laurence Salamatov and Innocent Shayashnikov who later produced volumes of church texts in the Aleut language. Fr. Laurence Salamatov produced Atkan translations of the Holy Gospels andCatechisms in the 1860’s, while Fr. Innocent Shayashnikov would go on tocomplete all four Holy Gospels, the Acts of the Holy Apostles, a manuscript prayerbook and a Catechism in Eastern-Aleut. His work was last printed in 1903, and served the Aleut faithful for over 100 years until the recent electronic re-publication of their texts on www.asna.ca/alaska. The disciples of St. Jacob learned well from their teacher, and their work nourished generations of Aleut Orthodox.

But the story doesn’t end there for St. Jacob. After a series of tragedies including the death of his wife and the burning of his house, he felt that he should become a monastic. However, the hand of God led him to minister to the interior of Alaska beginning in 1844, where he learned new languages and preached in the languages of the Kuskokwim region. Drawing upon St. Jacob’s work, Fr. Zachary Bel’kov compiled two prayerbooks, which were later published by the Diocese of Alaska in 1896.

These two texts remained as the sole published inheritance of St. Jacob’s flock until 1974, when a new Yup’ik language Hymnal was produced (and later revised in 2002) by Fathers Martin Nicolai, Michael Oleksa, and Phillip Alexie.

This may seem like a dry re-collection of dates and events, but what I find most incredible about these dates and names, is that from the efforts of two men — St. Innocent and St. Jacob — they gave Native Alaskans a literary tradition which was embraced and further developed by the Native Alaskans themselves. The works of Fathers Laurence Salamatov, Innocent Shayashnikov and Zachary Bel’kov are a testament to this. There were other authors, too, such as Readers Andrei Lodochnikov and Leonty Sivtsov who produced ecclesiastical and popular works in Aleut. The Aleut, Yup’ik, Tlingit and other peoples paid for the printing of their own texts, and it was they who maintained the oral tradition of their church hymns. It was also the native peoples themselves who kept the Orthodox flame alive in the face of American assimilationist pressure in the 20th century.

Much like Sts. Cyril and Methodius, the work of Sts. Innocent and Jacob planted the seeds of an authentically local Orthodox Church. When mis-guided people speak of Christianity as a foreign culture-destroying element, etc., this is completely false in the context of Alaskan Orthodoxy. Such popular thinking in the media is at best a misguided perception; at worst, it’s an outright lie.

The Orthodox Church in Alaska — its faithful, its priests, its stewards — is an organic, integral part of the fabric of the First-Nations, the native peoples, and of all peoples of Alaska.

Please pray to God for His continued blessing to be upon this project. Please pray for the eternal salvation of our souls, and for all Orthodox Christians in Alaska.

RTE: Amen.

RESOURCES ON NATIVE ALASKAN ORTHODOXY: BOOKS

St. Innocent: Apostle to America

by Paul D. Garrett - published 1979, SVS Press

www.svspress.com/product_info.php?products_id=3170

Currently available from SVS Press

Alaskan Missionary Spirituality

by Fr. Michael Oleksa - published 1987, Paulist Press

Out of print, used copies available online.

Orthodox Alaska: A Theology of Mission

by Fr. Michael Oleksa - published 1992, SVS Press

www.svspress.com/product_info.php?products_id=200

Currently available from SVS Press.

Journals of the Priest Ioann Veniaminov in Alaska, 1826 to 1836

by St. Innocent (Veniaminov), tr. Jerome Kisslinger - published 1993, Univ. of Alaska Press

www.uaf.edu/uapress/book/displaysingle.html?id=7

Currently available from Univ. of Alaska Press

Memory Eternal: Tlingit Culture and Russian Orthodox Christianity Through Two Centuries

by Sergei Kan - published 1999, University of Washington Press

www.washington.edu/uwpress/search/books/KANMEM.html

Currently available from Univ. of Washington Press.

Through Orthodox Eyes: Russian Missionary Narratives of Travels to the Dena’ina and Ahtna, 1850s-1930s

by Andrei A. Znamenski - published 2003, University of Alaska Press

www.uaf.edu/uapress/book/displaysingle.html?id=13

Currently available from Univ. of Alaska Press.

From Mask to Icon: Transformation in the Arctic by S.A. Mousalimas - published 2004, Holy Cross Orthodox Press

www.store.holycrossbookstore.com/1885652631.html

Currently available from Holy Cross Orthodox Bookstore.

WEBSITES

Russian Orthodox Diocese of Alaska: www.dioceseofalaska.org

Alaskan Orthodox Texts – Aleut, Alutiiq, Tlingit, Yup’ik: www.asna.ca/alaska

The North Star - official publication of the Diocese of Alaska:

www.oca.org/DOC-PUB-NS.asp?SearchYear=&SID=34

St. Herman Theological Seminary: www.sthermanseminary.org

Outreach Alaska: www.outreachalaska.org

Rossia Inc. - Russian Orthodox Sacred Sites in Alaska: www.rossialaska.org

The Russian Church & Native Alaskan Cultures: www.loc.gov/exhibits/russian

(U.S. Library of Congress exhibit)